The Missing Link in Performance Management

by Marcus Buckingham

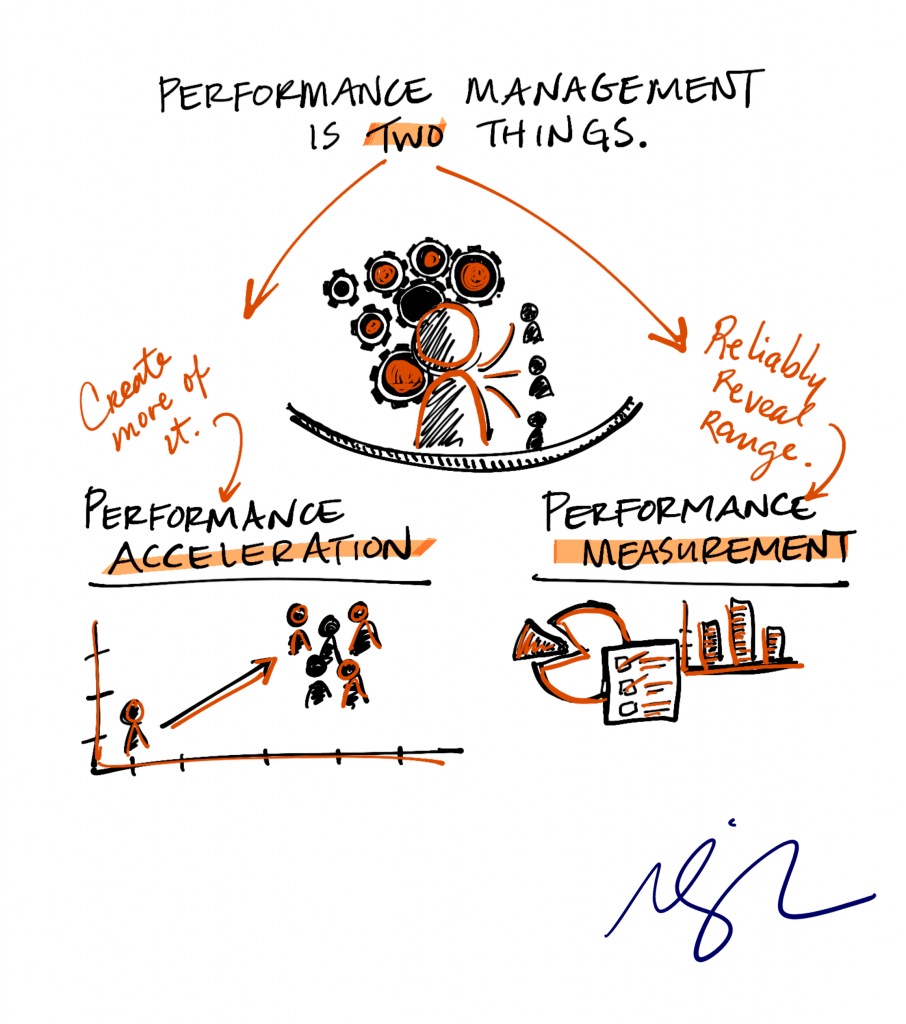

It is now a given that organizations are interested in overhauling their performance management systems. Nobody is satisfied with the systems of the past. The source of all the frustration is that we have lost our way in what we need to solve for. When we talk about performance management, we are not talking about one problem, but two distinct problems, which require two distinct solutions.

The first problem is one of performance measurement: how do we reliably reveal performance? Here the challenge is to find a way to see the true, unforced range in performance of each employee so that we can then invest differentially in our people. This is a measurement challenge.

Second, there’s the problem of performance acceleration: how do we create more or better performance? This isn’t a measurement challenge. Instead, it deals with issues such as how to pinpoint people’s strengths, how to focus and coach them, and how to engage them. It’s a development challenge.

Whatever we are looking to leave in the past, we can’t abandon either of these things. But if we try to solve them in the same way, at the same time, we will end up back where we started, with systems that satisfy no one.

One Stone, Zero Birds

Although “two birds, one stone” seems like a model of efficiency, in practice it is incredibly inefficient to tackle performance measurement and acceleration together. Let’s consider some common examples to see why this is so.

Example 1: OKRs

Some companies have put Objectives & Key Results in place, thinking these will accelerate performance. (Whether they actually do is far from clear, but for the sake of argument, let’s say they do.) But then we can’t help ourselves: these OKRs inevitably become become a core part of the way we measure performance. We create technologies that allow us to track how many OKRs each person has, what percentage completion each person has, and we then use this information to assess each person.

And in so doing we ruin OKRs’ ability to do either measurement or acceleration. Because when they are measured by their goal completion, people will adjust them down to make the targets more achievable. And all at once this system created to accelerate my performance causes me to lower the bar for myself, thus ensuring that OKR’s have the exact opposite effect to the one intended.

OKRs, by trying to solve for both problems, solve for neither.

Example 2: Feedback

We think feedback is useful for accelerating performance (whether or not that’s true, we’ll discuss later). But even if it is necessary, what happens when that feedback seeps into the measurement realm? “Hey, everybody needs feedback. Let’s get even more of it!” We’re going to aggregate that feedback from your bosses, and even your peers, over the course of the year, so that we can figure out what your performance was like and how to differentially invest in you. Oops. Now we’ve taken feedback from the acceleration bucket and poured it into the measurement bucket. The problem? When they know that their feedback is about assessment and not just acceleration, people skew their feedback.

Example 3: Competencies

Competencies were initially intended as a way to measure performance — at many companies, they represent strict evaluation criteria for whether an employee is prepared to level up. In the U.S. federal government, competencies are even written into law as the criteria for promotion into Senior Executive Service.

But as we all know, competencies never stay in their assigned little measurement compartment, do they? They creep over into the acceleration part of the equation. We use them to define performance for our people, and link them to our learning and training content. “Ah! There’s a competency gap! We’d better give you some learning content to train you on how to plug that gap.” So now we’re saying that in order to develop your performance and get more of it, we’re going to use this competency model. Unfortunately, whatever you think of competency models as a way to assess performance, there is no evidence at all that the way to accelerate performance is to identify a list of competencies and then tell people to go out and acquire the ones they don’t have. Any team leader will tell you this is a hugely inefficient way to accelerate performance, because you’re ignoring the starting point of performance: the person.

These are just three examples, but there are countless others, of how systems that try to solve for both assessment and acceleration at once wind up doing both badly.

So, what’s the right way to reinvent performance management? What would it look like to divide and conquer assessment and acceleration as two separate problems?

The First Problem: Performance Measurement

The key challenge in performance assessment is this: How can we reliably reveal the true range in performance so that we can invest differentially in each of our people? We’ll always need good data on which to make differential talent decisions. The problem is that our entire ratings edifices are built on the assumption that team leaders can be reliable raters of other people.

Unfortunately, this isn’t true. Decades of research reveals that we are all hopelessly unreliable raters of others. The challenge is something called the “idiosyncratic rater effect.” Put simply, it means that all ratings data actually reveal the rater, not the rate. Which is a problem, of course, since we end up paying, training, and promoting people as though their ratings reflects them. And they don’t.

This means that all of the talent data that we’ve been putting into our systems and using to evaluate and compensate our people is flawed. We are measuring, paying, and promoting people based on ratings data that reflect the rater, and not the person rated.

We should get rid of our current ratings systems because they generate fundamentally bad data—they measure the opposite of what they purport to measure. But this doesn’t mean we don’t need data. The challenge is to generate data that reveal the true range in performance and potential of our people, and to do so in a way that solves for the idiosyncratic rater effect.

Fortunately, there are ways to address this—beautifully simple, methodologically sound ways. In general, it boils down to these three steps, in ascending order of simplicity:

- Invert the rating questions. You cannot ask people to rate other people, but you can ask them to rate their own intentions regarding them. So, our first step is to ask team leaders what they would do with each employee. Will each team leader be subjective? Of course. But that’s precisely the point. We don’t want to remove people’s subjectivity; instead we want to measure it reliably.

- Identify each team leader’s rating ‘fingerprint.’ This is easier than it sounds. Once you have identified the few questions to ask team leaders, you can then see the unique rating pattern of each team leader and use an algorithm to neutralize the uniqueness of each team leader. This algorithm not only solves for the idiosyncratic rater effect; it is also fairer.

- Weight the data by ‘frequency of interaction.’ These days most work is done on ad hoc project teams. As such the ratings of a team leader who has worked with you for four months ought to have a third of the impact of a leader you’ve worked with for a year.

The Second Problem: Performance Acceleration

We’ve all come to realize that our annual performance reviews are ineffective ways to accelerate performance. Some organizations have addressed this by creating a cadence of more frequent reviews. But just as more bad data doesn’t somehow magically produce good data, you can’t take a process that everybody dislikes and finds irrelevant, and solve it simply by making it happen more frequently. We won’t solve the acceleration problem by expanding an ineffectual HR process. Instead, we need to look at what the best team leaders actually do to accelerate performance and replicate that.

A significant body of research—by TMBC, Gallup, and others—shows the most predictable drivers of performance and engagement. The answer lies in two simple questions:

- At work, do I have the chance to do what I do best every day?

- Do I know what’s expected of me at work?

Address these two questions successfully for every employee, and the data show that you will drive performance. The best team leaders get people to say “yes” to those two questions with one ritual: frequent, one-to-one light-touch check-ins about near-term future work. Let’s break this down:

- Frequent: This means once a week.

- One-to-one: Human beings are attention-seeking creatures, and the one-to-one check-in is a way to inject more individualized attention into the system.

- Light-touch check-ins: These are 10-minute conversations that address two questions: What are you working on? And how can I help?

Near-term future work: These conversations are not built around feedback from the past. They’re focused on coaching for greater success in the future.

The frequent, light-touch check-in is not a new ritual. It’s what the best team leaders already to accelerate performance. The challenge for us all will be to figure out way to get all team leaders to do what the best do.

The Missing Link (AKA, “They’re Digging in the Wrong Place!”)

There’s a scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where Indiana Jones realizes that his enemies are missing a key link in the instrument that points the way to where the Ark is buried. They only have half of the picture, and their system is therefore all wrong and doomed to fail. In unison with his friend, he jubilantly realizes and exclaims, “they’re digging in the wrong place!”

As with Indy, so with us. We need to realize that we have a missing link. We’ve been missing the fact that performance management is two different problems, each requiring its own distinct solution. This means we’ve been digging in the wrong place, but this realization should excite us. Because it’s the first step on the road to the future.

Marcus Buckingham is a world renowned performance thought leader that relentlessly seeks the fundamental truths that help people unleash and break their performance boundaries.

For over 2 decades, Marcus has been on mission to build a world where people are passionate about finding love in their work. His vision is to unite individuals from across the globe, to create the most impactful community of people that believe everyone has boundless potential. We would love to invite you to learn more about the LOVE+WORK movement.